1976-2025: Pamela Gilbert’s Ritual Integration Performance at the Experimental Art Foundation

Essay by Alexandra Nitschke, 2025

In May 1976 Pamela Gilbert performed Ritual Integration Performance at an exhibition opening in Adelaide. It was a bold and captivating performance, and the first documented artwork by Gilbert. It also appears to be her last.

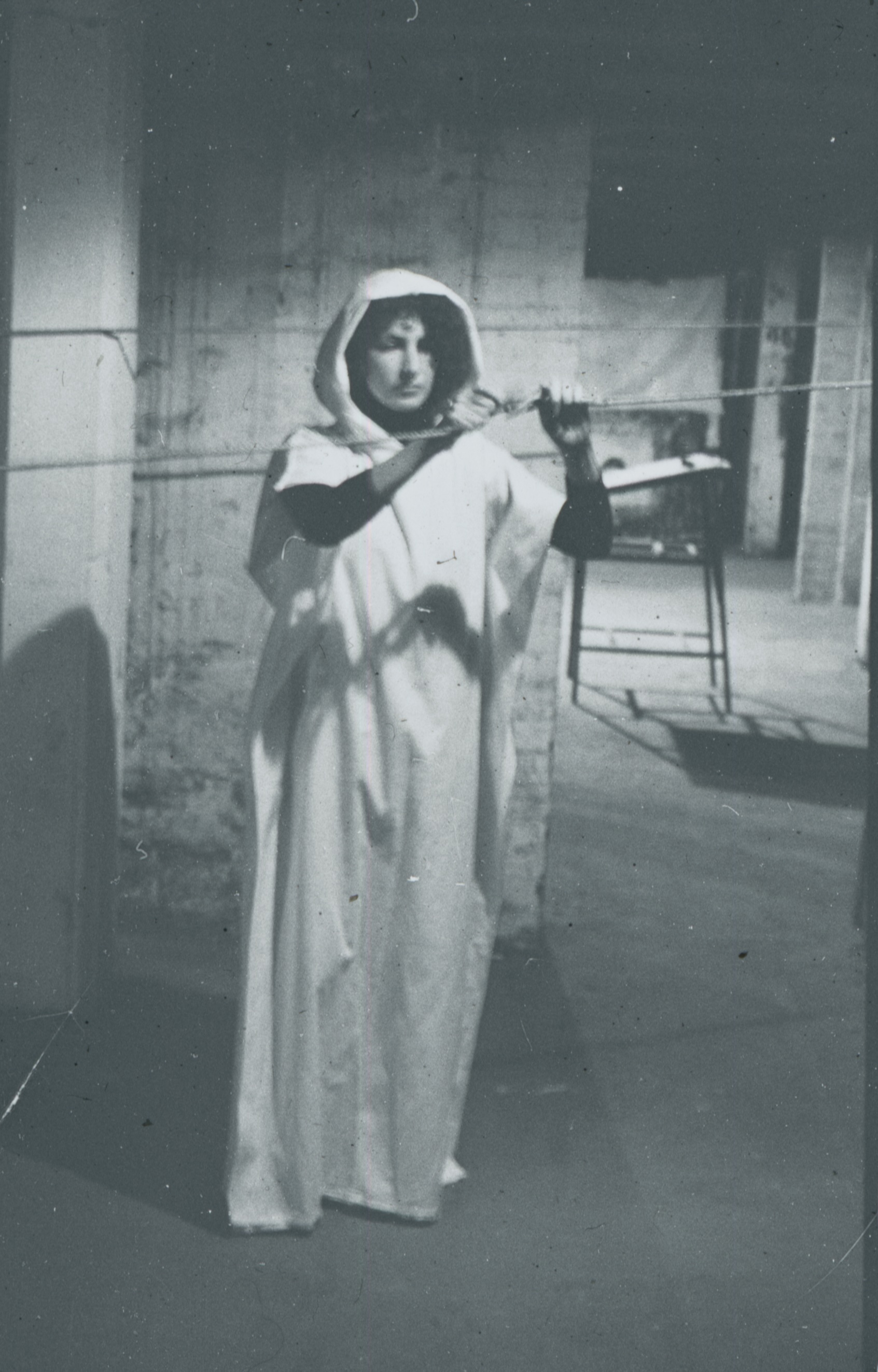

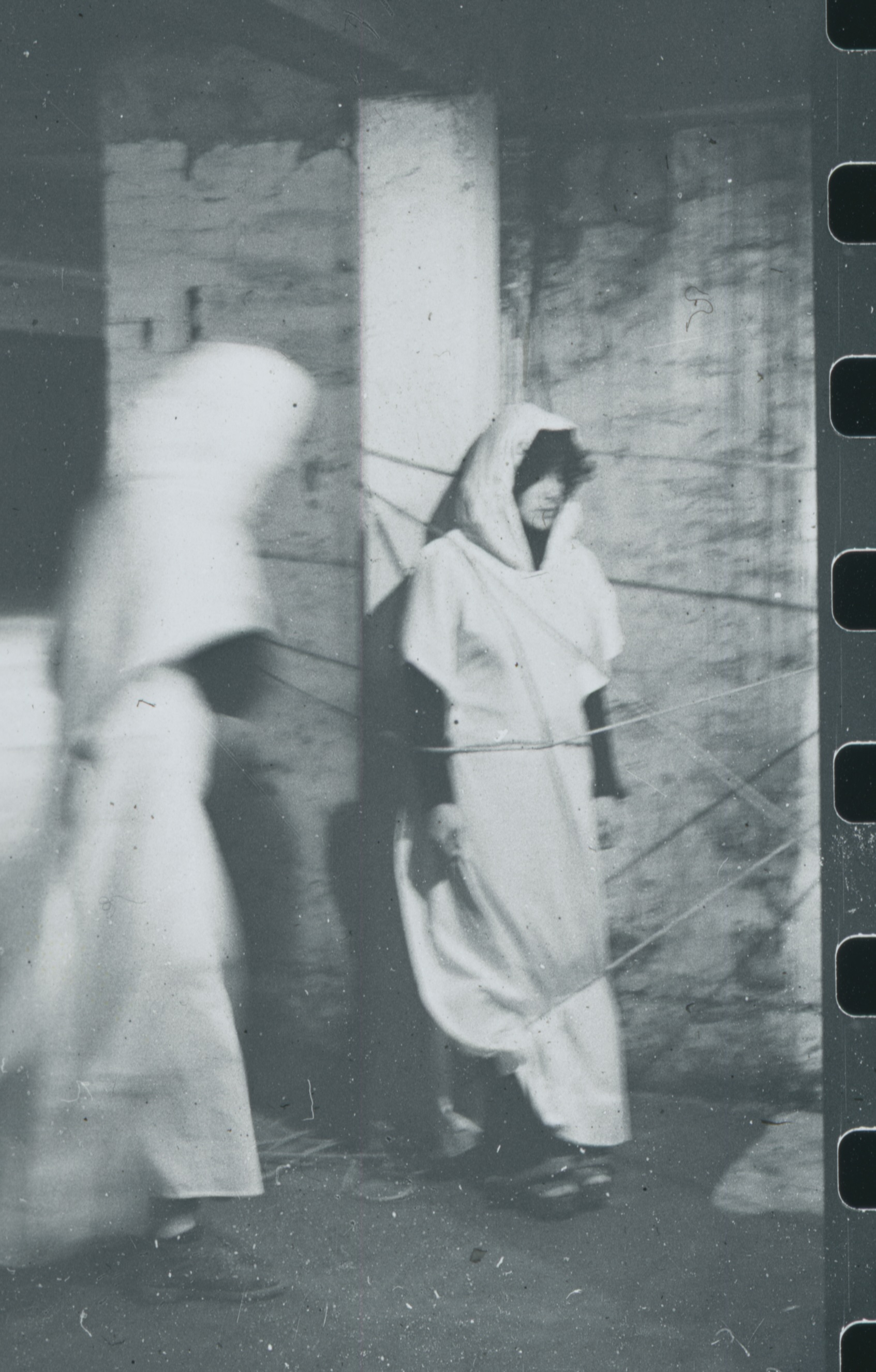

Taking place in the basement of a new, radical artspace on the fringe of the Adelaide CBD, Ritual Integration Performance blended people, shadow, ritual and environment. It was conceptual and experimental. Bright spotlights on the performance created contrast and shadow within the darkened underground room. Three performers wore white robes with hoods and traversed the space tying rope between pillars. They then bound a figure to a concrete post, and later, embraced. The soles of their shoes were painted with white paint to display their footprints. In undeveloped photographic negatives, the white figures appear like ghosts, their movements blurred within the concrete space. It’s a dramatic and intriguing scene.

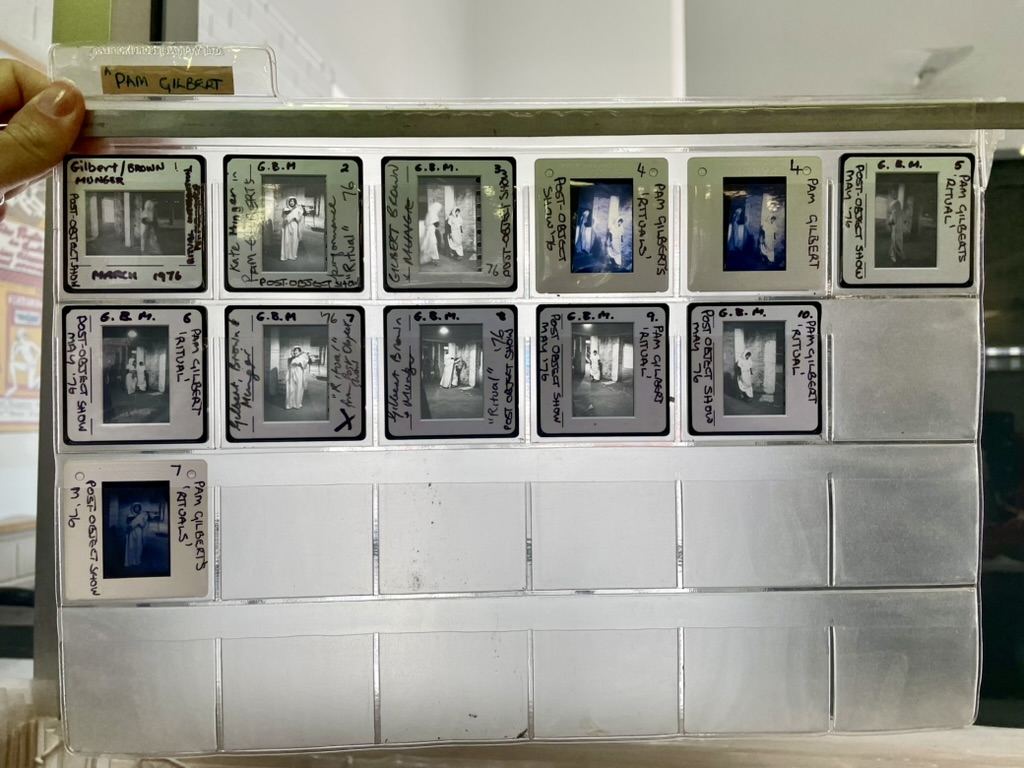

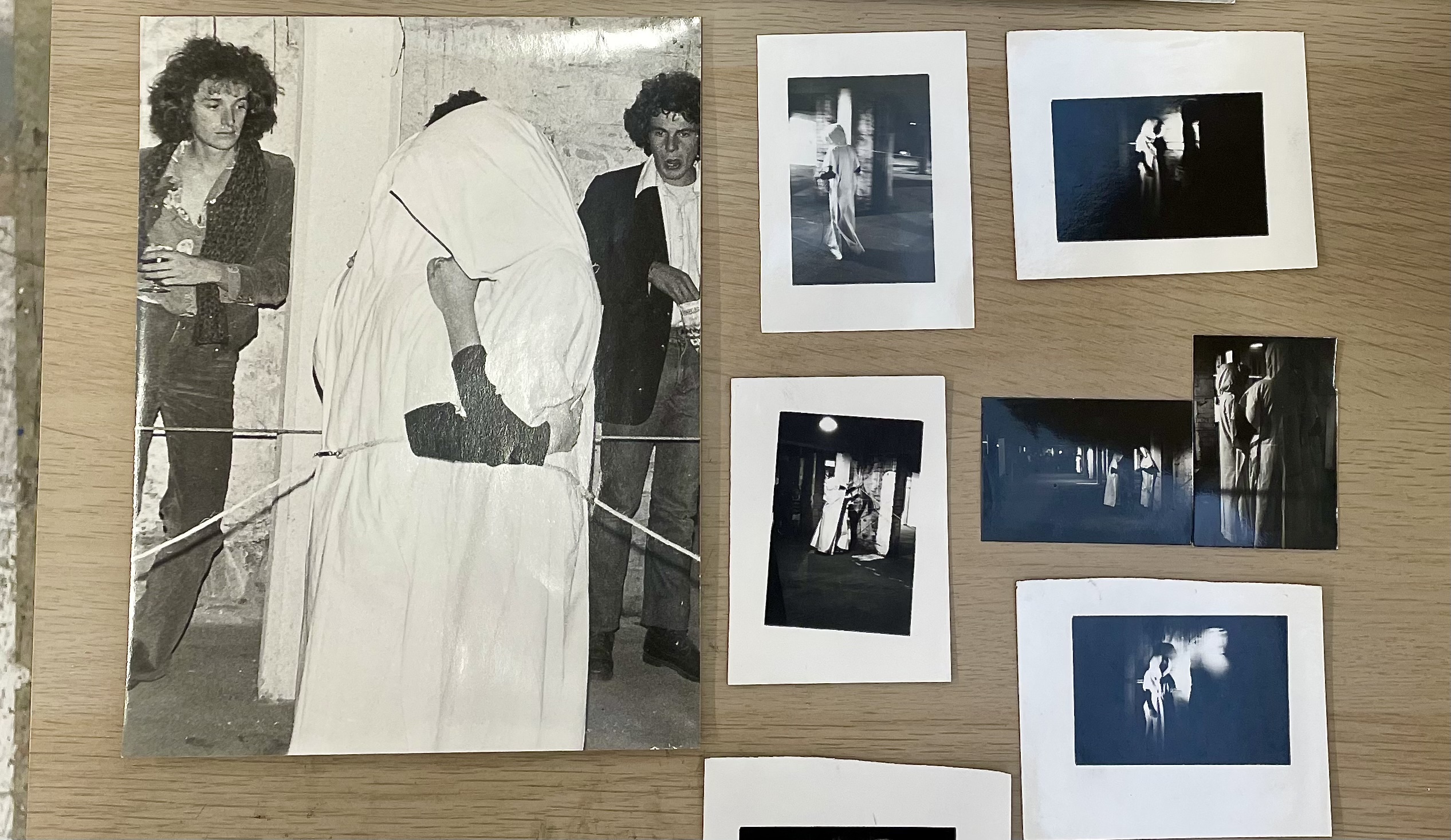

The performance itself was never filmed – still photographs and undeveloped negatives are the only trace that remains. And while they reveal a record of the event, their grainy, unfocused, snapshot qualities also conceal.

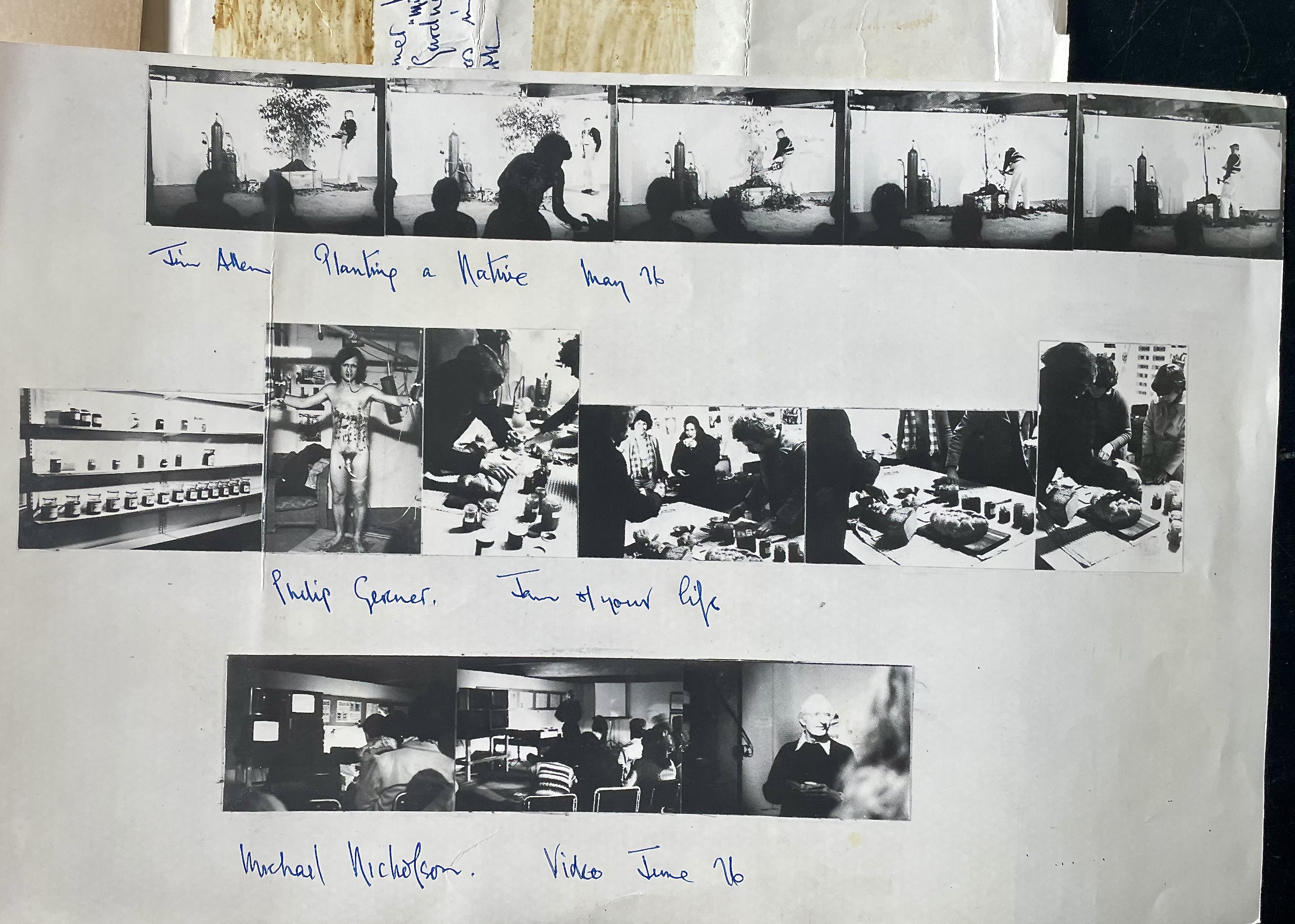

It is through a connected research subject that I come across these photographs and negatives in the bottom of an old office filing cabinet. They’ve been there for decades. I wonder if anyone else has come across them over the years. The filing cabinet is full of documented performances and exhibitions. It’s a treasure trove of past happenings, lectures, performances and experimental acts, publications, and ephemera. There are photos of the time Jim Allen took a chainsaw to a native sapling in On Planting a Native (1976), and when Jill Orr had her hair cut by audience members to a soundtrack of male jeering in She had long golden hair (1980). A suspension work by Stelarc in 1990 is captured in small slides, as well as a 26-hour endurance performance by Stuart Brisley. Many of these events feel familiar – part and parcel of an introduction to performance art in Australia. Perhaps this is why I feel drawn to Pamela Gilbert’s Ritual Integration Performance (1976). Neither Gilbert nor her performance have received the same attention nor acclaim as these more famous works of performance art taking place in Adelaide.

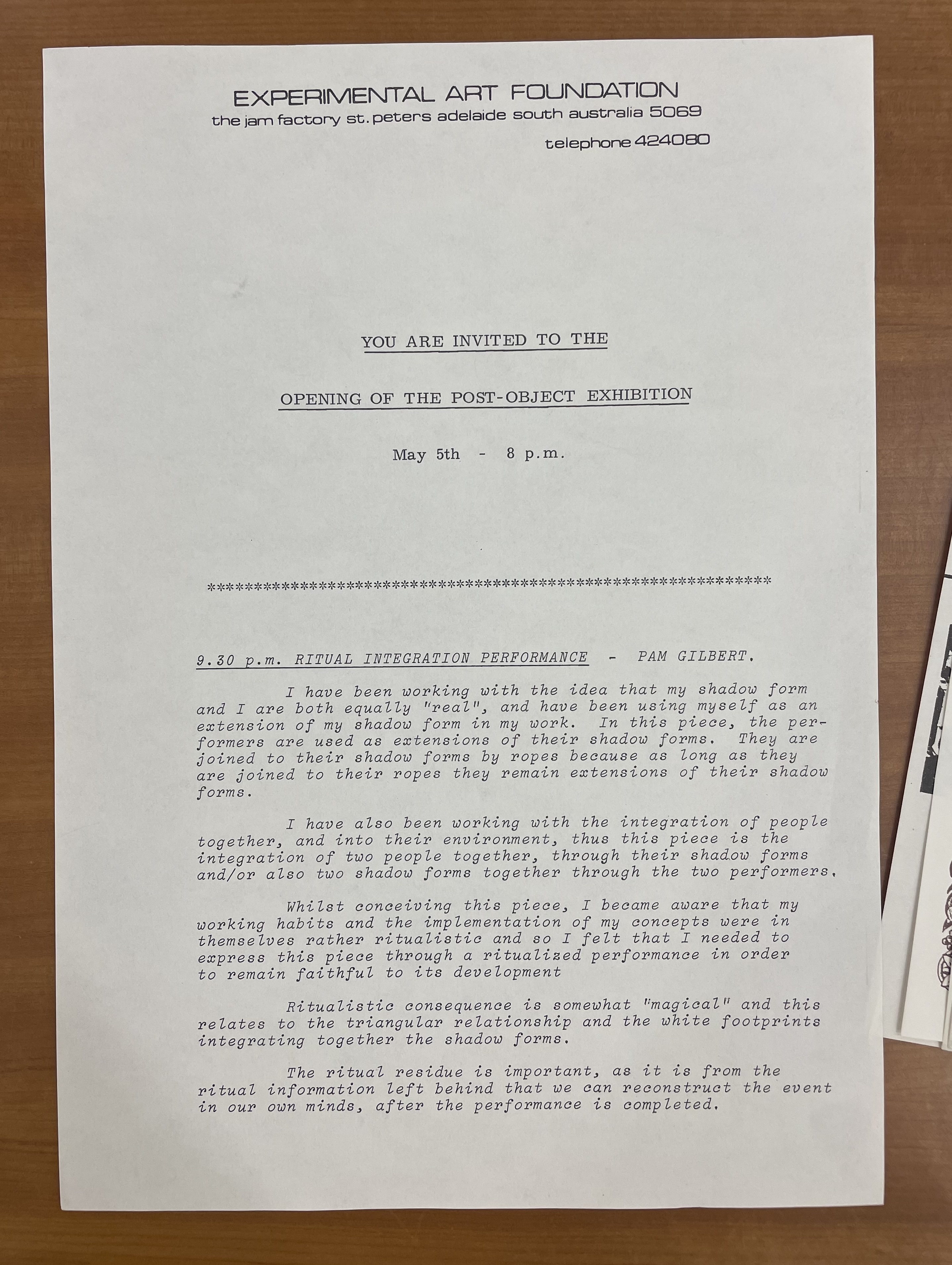

Gilbert’s performance took place at an exhibition opening in the old Jam Factory on Payneham Rd. It was the first major exhibition by the Experimental Art Foundation (EAF), a newly-established, radical organisation dedicated to the idea of art as an ‘arena of open experiment’.1 The exhibition was similarly new and radical. Ambitious in scale and scope, it indicated the aspirations and areas of focus that would set the EAF apart from other contemporary art organisations. At a time when being an artist was often synonymous with being a painter, the exhibition established the EAF as a centre ‘for new and radically different art forms’.2 The exhibition, titled Australian and New Zealand Post Object Show – A Survey included performance, installation, happenings, lectures, video, dance, photography, and texts. Public response was mixed: some regarded it ‘as highly stimulating – a new force, the next step forward’, while others met with exhibition with ‘much bewilderment and despair’.3 Some of the performances were durational. Philip Gerner’s naked The Jam of your Life took place across 36 hours whereby the artist was fitted with a nasal tube and catheter, and acted as a ‘jam-tasting facility’. Jim Allen’s Elastic-Sided Boot involved a group of participants attempting to communicate with each other through sound-making objects in an area encircled by a strip of 35mm film holding images of a recent shooting. In another part of the exhibition was an installation (in the language of the day, an ‘environment’) comprising a family of half human, half-locust mannequins watching TV in their lounge room by Bonita Ely, titled C20th Mythological Beasts: at Home with the Locust Family. The EAF was a place where artists could show and make artwork free from the constraints and pressures of working within (conservative) traditional institutions or commercial systems. It was radical and experimental, and there was a sense of the boundless possibilities of contemporary art. This landmark first exhibition embodies this, and arguably sets the tone for the organisation for decades to come.

Pamela Gilbert’s Ritual Integration Performance holds an important position as the exhibition’s sole opening night performance. The performance is featured on the exhibition invitation with an outline of its conceptual foundation, and is the only work to be highlighted in this way. The performance was fairly well documented and it is clear it was seen by a large crowd. Gilbert was 28 years old, and in the final year of her Diploma in Fine Arts at the SA College of Advanced Education. She was majoring in Sculpture at a time when the medium was beginning to be extended ‘into temporary, multi-part, mixed media, largely ephemeral situations’4 loosely described as ‘post object art’. It was an exciting moment. Traditional ideas about art were being tested and dismantled, and new alternative arts spaces were providing space to engage audiences. The Whitlam Government had radically restructured the Australia Council for the Arts and increased fiscal support, providing new opportunities for artists and arts organisations. From the beginning, EAF was provided with a modest stipend, though it was primarily powered by donations and a large group of volunteers. It was a dynamic creative and intellectual environment. For Gilbert, an opening night performance represented an opportunity to engage audiences with her theoretical interests and to test herself, her work, and her ideas within a public space. As her first artistic performance it was an important testing ground, and a significant step in her artistic career.

The performance itself was intriguing and dramatic, arising from Gilbert’s conceptual exploration of the human shadow. Within the performance Gilbert flips the common perception of a shadow following a human form, and instead considers the inverse: the human form as an extension of our shadows. It’s unclear whether this was a symbolic exploration of our shadows – was Gilbert exploring the notion that our darker side is our primary driver? At one point in the performance, at least one performer is tied to a concrete post with rope. They all wear white robes with hoods, which glow under bright spotlights. Dark shadows are cast across their faces and over the floor. Later, two figures embrace, loosely bound together with hooks and rope. This may be the ‘integration’ of shadows Gilbert speaks of in her artist statement, a joining of people through their shadow ‘forms’. Religious connotations appear to run throughout the performance: in the costume choice, the dramatic contrast in light and dark, the inclusion of three performers, and the ambiguous ‘ritualistic consequence’ that Gilbert also notes in her artist statement. Footprints and small sections of the basement wall and floor are painted during the performance. One photograph shows a performer holding a tin of paint and a wall brush, and another shows painted panes on the wall and floor – traces that remained following the event itself. The EAF has since relocated twice, though I can’t help but wonder how long the paint was left there.

Today, all that remains of the performance are several black and white photographic stills, some undeveloped negatives, and an artist statement. There is almost no other trace of Pamela Gilbert in the old filing cabinet or in the many archival boxes stacked in the compactus. Our attempts to piece together the puzzle reveals many gaps. We know Gilbert went on to achieve a First Class Honours degree in Visual Arts and Drama at Flinders University in 1980, and following this, a Masters of Arts in Theatre in 1983. Two years later she produced a book titled Women in Japanese Theatre based on her Masters research. This indicates her ongoing interest in parallel disciplines – performance, drama, and theatre. Ritual Integration Performance, however, appears to be her first and final performance work. The EAF held regular Friday night performances – yet there’s nothing to indicate further performances by Gilbert. A decade on from this first performance at EAF, Gilbert took up an Administrator role at another volunteer-run art organisation in Adelaide, the Contemporary Art Society (CAS). The CAS was described as ‘middle of the road’ in contrast to the EAF’s radical experimentalism, its membership numbering more painters than performance artists.

During this time in the mid Eighties, Gilbert was also Editor of the CAS Broadsheet, a quarterly art journal. Gilbert made significant improvements to the journal during her 18-month tenure; however, we lose sight of her whereabouts following her resignation in June 1985. We know she was married six months earlier, between December 1984 and January 1985, and her surname was thereafter hyphenated: ‘Gilbert-Falkenburg’. Many of those involved in the original exhibition and the establishment of the organisation have now passed. Some of the artists have continued to produce work, while others have seemingly stepped away from their artistic practice to follow other paths. Some were later married and changed surnames, had children, possibly relocated. Perhaps this was Gilbert’s path.

Ritual Integration Performance comprised three performers: Gilbert, Kate Munger, and someone listed as Brown. We have loose leads on who Brown was, however these are unconfirmed. We haven’t found any information on Munger. Perhaps they were friends involved in the presentation of the performance, but otherwise uninvolved with the organisation. Perhaps they were partners of male artists involved at EAF. It’s also unclear whether the performance was accompanied by sound, or what the duration may have been. Were the robes white? It’s possible light yellow, or another pastel shade, could appear white when brightly lit by the spotlights in a dark space and processed in monochrome. The snapshots of the performance are limited in the information they can provide us, fifty years on from the event. We can’t possibly understand the experience of the performance, no matter our level of curiosity. As a record of a live event, performance art documentation is inherently contradictory in terms. You had to be there.

Yet each time I look at the photographic stills of Gilbert’s performance or the undeveloped negatives I can’t help but notice something new. Some small detail I hadn’t noticed the first few times I had examined the images. The rope curled on the floor beside the bound figure, their platform shoes, the subtleties in the audience’s reactions, the small inflections across the concrete floor and walls catching the light. It’s possible these photos are more than merely traces, more than merely documentation. They conceal, and reveal. They can offer insights and discoveries potentially missed in the original experience of the performance event, enabling the chance to ‘see details that you hadn’t noticed because you were there but you couldn’t be looking everywhere’.5 They offer worlds awaiting discovery and deep layers for unearthing. They are a parallel perspective offering stillness and pause to the movement, sound, and texture of the performance event.

The photographs and undeveloped negatives of Ritual Integration Performance are powerful and captivating images in themselves, capturing our attention and stirring our curiosity fifty years on. They’re also a pathway into a performance work seemingly overlooked. Gilbert never achieved the same attention or acclaim as her fellow male artists who also performed at the EAF. And despite presenting her work at the opening of the first major exhibition of a new and radical art space, it didn’t receive commentary or review, at the time; or later. The grainy, unfocused snapshots hiding away in the bottom of the old filing cabinet give us the chance to connect with a work otherwise seemingly forgotten, and shed light on female-led performance in Adelaide in the 1970s.

This essay was compiled with special thanks to Danni Zuvela, Henry Wolff, Jingwei Bu, Cameron Fleming, and the staff at the State Library of South Australia, specifically Tasha Eskau and Chris Read.

Alexandra Nitschke, 2025

❶ Brook, Donald. “The Experimental Art Foundation.” Art and Australia, vol. 12, no. 4, Apr. 1975, pp. 378–80.

❷ Britton, Stephanie. A Decade at the EAF: A History of the Experimental Art Foundation 1974-1984. Experimental Art Foundation, 1984, p. 36.

❸ Ward, Peter. “Non-Look at Non-Art.” The Australian, 11 May 1976.

❹ Barton, Chrisitna. “Post-Object and Conceptual Art – What is Post-Object Art?” Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, 22 Oct. 2014, www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/post-object-and-conceptual-art/page-1. Accessed 20 Mar, 2025

❺ Goldberg, Roselee. “How RoseLee Goldberg Reshaped the Landscape of Performance Art.” The Slowdown, interview by Spencer Bailey, 27 Sept. 2019, timesensitive.fm/episode/roselee-goldberg-performa-reshaping-performance-art/. Accessed 15 Mar. 2025.